What is Big Fashion doing?

I barely even know what the word sustainable means anymore.”

The clues that the fashion industry is wildly unregulated are seen in the deluge of words printed onto clothing labels: eco, eco- innovative, recycled, upcycled, vegan, fair wage, fair trade, locally made, carbon neutral, organic, made with renewable energy, made with love, circular, biodegradable, zero waste. These words, which can be made up and printed at random, stand in for legislation and provide a cover for unethical corporate behaviour.

In September 2022, the Netherlands Authority for Consumer Markets ruled that terms “Ecodesign” from Decathlon and “Conscious” from H&M were unclear or insufficiently substantiated. It told the two fashion companies to stop making misleading sustainability claims on their clothes and websites.59

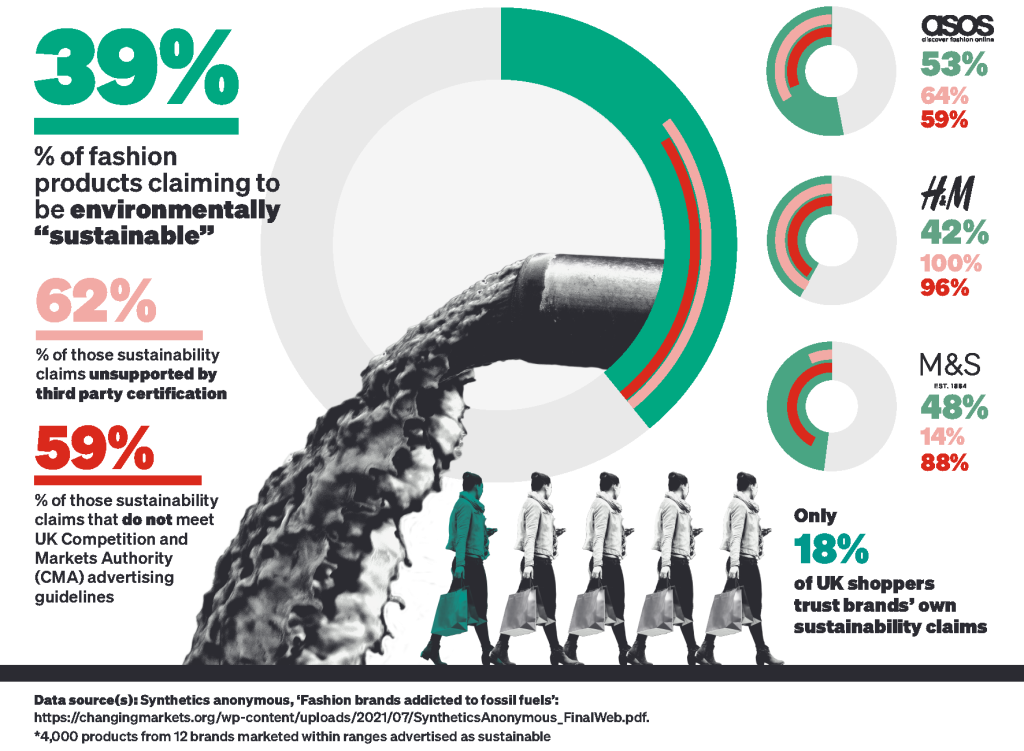

This was not the first time H&M’s heavily- marketed ‘conscious’ collection has come under scrutiny. One recent study into synthetics found that H&M’s ‘conscious’ range actually contained a higher percentage of synthetics than its main collection – 72% versus 61%. The same report analysed 12 brands and 4,000 products, discovering that brands routinely deceived consumers with false claims. While 39% of the products studied had some kind of green claim attached to them, 59% of these claims flouted the guidelines set by the UK Competition and Markets Authority. The worst offenders were H&M with 96% false claims, ASOS with 89% and M&S with 88% false claims.60

Further crackdowns on greenwashing are expected, with H&M facing a class action lawsuit in the US; and Boohoo, George at Asda, and ASOS being investigated by the Competition Markets Authority in the UK.61 It is little wonder that the public has lost faith in fashion’s green claims.

One 2020 survey found that 81% of EU citizens do not trust the environmental claims listed on clothing products.62

Behind the labels and the mistrust is a worrying landscape. Big fashion lacks transparency and there is a lack of reliable global data or peer-reviewed research into fashion’s environmental impact. Estimates of the global greenhouse gas emissions from fashion vary wildly from 1.8% up to 10%.63

For an industry that overwhelmingly produces non-essential items, if either of these figures is correct, it is far too high.

Big fashion is showing no credible sign of meeting international climate goals. The UN predicts emissions from fashion will increase by nearly 50% by 2030.64 Similarly, a 2019 survey of 62 major clothing brands found that less than a quarter had any kind of target set to reduce water pollution, and only 6% were monitoring progress against these targets.65 An additional study from The Climate Board found no correlation between stated climate commitments from brands and actual carbon reductions.66 Similarly, the New York Times reported in 2022 that over 200 million trees are cut down every year to produce man-made cellulosic fabrics such as viscose and rayon.67

Self-regulation in the form of certification or voluntary initiatives has failed.”

68

The proliferation of certification schemes has grown, as fashion has become one of the world’s most polluting industries. There are now over 100 sustainability certification schemes in use in the fashion and textile industry. A 2022 study by the Changing Markets Foundation (CMF) analysed the ten most popular of these initiatives, all of which are voluntary. The findings were extremely damning, with CMF stating most of the initiatives “fail to meaningfully uphold high levels of ambition and thus merely provide a smokescreen for companies.”69

Such schemes are instantly compromised by the fact they are paid for by the very corporations they are supposed to monitor. As well as exposing a lack of transparency and independence, the stifling of debate or alternative models, and an inability to call out paying members, CMF concluded that the very existence of these certification schemes allows big fashion to actively delay progress – with fashion companies able to sign up to multiple schemes whose distant targets just ‘kick the can down the road’ whilst giving the brand a veneer of active responsibility. This pretence at action derails more concrete means of change such as the passing of legislation, with big fashion able to point at schemes and say progress is in hand.

Voluntary schemes also tend to take a seemingly arbitrary focus on a garment’s life cycle. This obfuscation of the overall picture allows big fashion to shape the entire conversation around sustainability.

Picking and choosing a patchwork of certifications and initiatives also means that the systemic issues around fast fashion, reliance on fossil fuels and overproduction are neatly avoided, allowing companies to keep their skeletons in the closet and distract consumers from the industry’s wider environmental impact.”

70

In 2009, Patagonia and Walmart created the Sustainable Apparel Coalition which developed the Higg Materials Sustainability Index. The Higg Index lists polyester, which is made from petroleum, as the most sustainable of all fibres, leading critics to state that the entire scheme was created to greenwash fossil fuel manufacturing. In a recent blow to the credibility of the Higg Index, the Norwegian Consumer Authority recently ruled H&M and an outerwear brand called Nørrona could no longer use ‘environmental’ clothing labels based on the Higg Index.71

The truth is that serious change will be lengthy and expensive with one estimate stating it will take a trillion dollars in global investment to decarbonize the industry.72

The alternative, however, has a much higher price tag.

Change the world, not just your wardrobe

Well-meaning attempts to change the fashion industry’s environmental impact tend to focus on individual lifestyles and moralistic personal approaches to buying, caring for, and disposing of clothes. Yet in terms of carbon emissions, the production of fashion (including transport) accounts for an estimated 80% of a garment’s impact.74 (Where this calculation varies, even low estimates place this figure at 60%.75 ) This means that the vast majority of harm done by the fashion industry is a result of production decisions made in corporate supply chains.

Unlike its fossil fuel friends, the fashion industry appears to have gotten ahead of the sustainability problem first by acknowledging it, then by pumping tens of millions into developing its own gold standard for sustainability, creating a closed loop of shared stakeholders with nobody to hold them to account.”

73

While making low-carbon, environmentally- friendly choices is important, placing all the emphasis on individuals detracts from our drastic need for structural economic change. Nor will we convince ordinary people that they have a place in the movement for transformational change if we bombard them with repetitive, apolitical messages of guilt and shame.

Economics professor Jayati Ghosh says we must also consider the full picture with any green initiative – what actually happens to recycling after you put it in a green bin? Where has the lithium in solar panels been extracted from and with what consequences?

“You can’t simply say, well, I am being good in my little area,” Professor Ghosh argues. “You being individually good is never going to be enough if all the incentives in your economy are going the other way. I can be good in my individual habit, but if I’m part of a broader ecosystem, in which 80% of consumption involves really a lot of waste, or unnecessary plastic, or heavy emissions then it’s not useful.

I should be campaigning to insist on different standards. You can’t just say I’ll be good myself. You have to demand policies that make everybody conform.”

A narrow focus also ignores the terrible legacy of environmental destruction built up by big fashion over many decades. Nandita Shivakumar, at the Asia Floor Wage Alliance, says that to properly confront sustainability we must reject the narrow definition proliferated by the fashion industry.

“The current understanding of sustainability of big fashion brands refuses to solve or even acknowledge the climate crisis caused in the Global South already by the fashion industry and their purchasing practices,” Shivakumar says.

For example, industry reliance on cotton has meant that central Asia’s Aral Sea, once the world’s fourth largest lake, has already been turned into a desert, with 25,000 square miles of seabed now exposed in a disaster that has reduced the stability of the climate of the entire region.

The second danger of allowing corporations to define ‘sustainability’ so narrowly is, Shivakumar says, “the creation of an artificial separation between ecological issues and labour rights. Big brands are willing to pay millions to carbon reduction, but not even a few thousand dollars for severance or unpaid wages during a pandemic. This is very telling – it shows that brands care about sustainability when it affects customers in the West (as the climate crisis will have direct and indirect impacts on all), but they don’t care if the Asians producing for them starve from hunger. It’s a way of saying certain lives matter more than others. We need to stop brands from selling this narrative of sustainability to us.”

This branding of sustainability also extends into coverage of the fashion industry with a heavy bias towards environmental issues rather than workers’ rights. The neglect of workers’ rights is a key reason big fashion gets to maintain the illusion that the sector is ‘sustainable,’ and part of the solution to the climate crisis and social progress – instead of being a major emitter and cause of harm. Clean Clothes Campaign is very clear that “no major clothing brand is able to show that workers making their clothing in Asia, Africa, Central America or Eastern Europe are paid enough to escape the poverty trap.”76 This means big fashion is flouting human rights as well as their own codes of conduct. Using the global economic system that drives down prices and creates competition between countries, factories, and workers, big fashion pays a pittance while raking in billions in profit.

The creation of an artificial divide between workers’ rights and the climate crisis disrupts the need for a holistic view of the fashion industry, which shows the parallels in how poorly people and planet are treated. Ecological and climate damage, poverty and inequality have the same systemic causes – yet in the same way that social debate has become polarised between ‘workers’ and ‘planet,’ corporate solutions replicate the patterns of sacrifice zones by failing to address systemic causes.

Dumped

“We collect a lot of Tommy Hilfiger, a lot of H&M, a lot of Zara, sometimes I ask brands – where do we bring those items so that you can recycle them? Well, they are not interested in that.” Elmar Stroomer is the Co-Founder of Africa Collect Textile (ACT). “You ask a big brand why do you not use your used clothes as feedstock for new ones? But they don’t want their old clothes back, because they are still – in 2023 – not applying eco-design or design for circularity criteria when they design stuff.”

The refusal of big fashion to adopt circularity means the world has a massive textile waste problem – with an estimated 80% of end-of- life garments ending up in landfill or incinerators.77 Circularity of material and resource use is the idea that you only ever borrow a resource from a central pot of resources and must be able to justify using it and be able to return it to the pot to be used again.78 The fashion industry is the antithesis of this, with clothes designed as one-off items, and big fashion taking no responsibility for what happens after it has profited from an item’s sale.

You ask a big brand why do you not use your used clothes as feedstock for new ones? But they don’t want their old clothes back, because they are still – in 2023 – not applying eco-design or design for circularity criteria when they design stuff.”

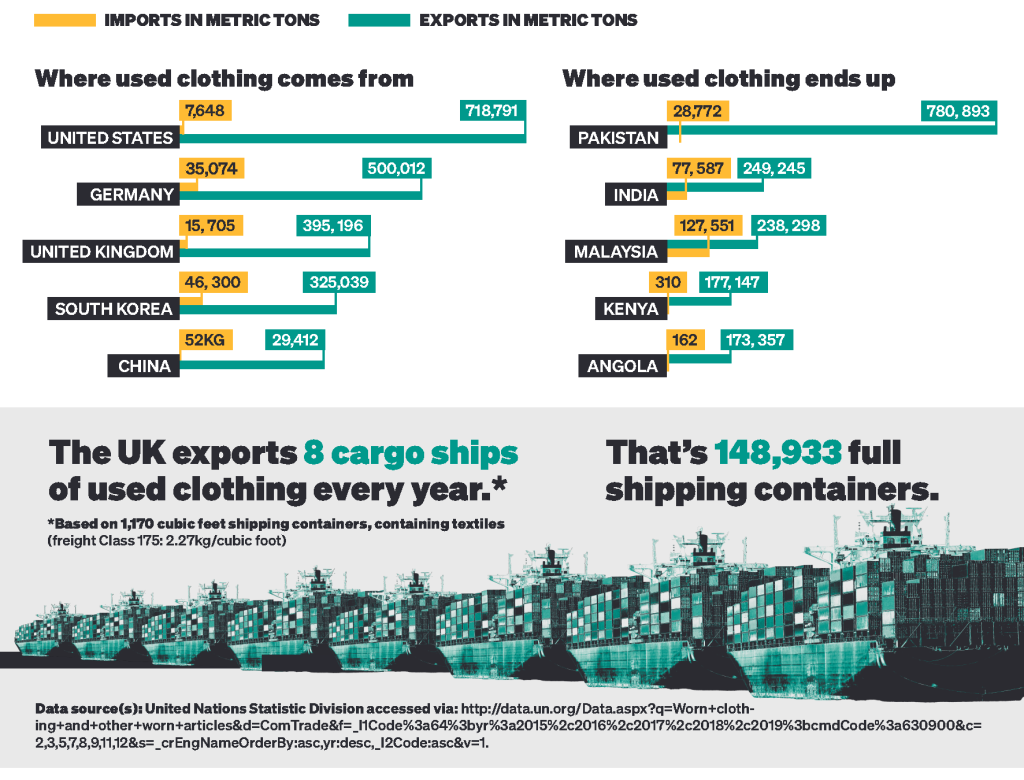

Once clothes get categorised as waste in the Global North, one place they end up, via private recycling companies, is Kenya. These exports generate vast profits for companies and governments, but the environmental and social damage they create was recently highlighted in the Trashion report by Changing Markets Foundation. This report estimated that each year, over 300 million items of damaged or unsellable clothing made of synthetic or plastic fibres are exported to Kenya, where they end up dumped in landfill, clogging up rivers, or burned – adding zero benefit to Kenya’s second-hand clothing market.79 Similar crises are taking place in Chile’s Atacama Desert and in Ghana.

It is a situation Elmar Stroomer and his business partner Alex Musembi are highly familiar with. They argue that without any infrastructure, dumping millions of tonnes of waste in Africa hurts everyone – microplastics going into the ocean, carbon dioxide from burnt textiles, and methane from landfill is not only a Kenyan problem. “You should realise that you are far from done by just sending that waste over here,” Elmar Stroomer says.

ACT has a network of clothing collection banks in Kenya. Donated clothes are carefully sorted and either redistributed or upcycled into items such as backpacks or rugs, or downcycled into filling. ACT also takes responsibility for recycling the workwear of private security firms who cannot risk their old uniforms falling into the wrong hands.

ACT say Kenya is an interesting place to be developing textile circularity, as east Africa is one of the regions where there is potential for a closed loop. Cotton can be grown, there is an existing infrastructure of spinning mills, weaving facilities, and garment factories – which currently make clothes primarily for export. If locally-made clothes weren’t exported, materials could be recovered, sorted, and placed back into the same systems that created them. A regional closed loop could be created.

But in the meantime, ACT say it would cost €20 million to process a single year’s worth of second-hand exports from the UK alone. “The EU and the Global North need to invest here in local infrastructure,” Alex Musembi says. “It’s very difficult to get that money – unless people are willing, unless there are laws, unless people are shouting more – that is when they will do it. Something must be done, money must be invested into Africa if we are to process even more of their materials.”

- 58Stella McCartney ‘Barely Knows What Sustainable Means Anymore’. Fashionista. 8 October 2020. Whitney Bauk. https://fashionista.com/2020/10/stella-mccartney-spring-2021-collection…

- 599 Deeley R. H&M, Decathlon Dial Back Claims to Dodge Greenwashing Crackdown. The Business of Fashion. 13 September 2022. https://www.businessoffashion.com/news/sustainability/hm-decathlon-to-m…

- 60Synthetics Anonymous Fashion brands’ addiction to fossil fuels. Changing Markets Foundation. June 2021. http://changingmarkets.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/SyntheticsAnonymo…

- 61Asos, Boohoo Targeted in UK Greenwashing Probe. The Business of Fashion. 29 July 2022. https://www.businessoffashion.com/news/sustainability/asos-boohoo-targe…

- 62Dirty Fashion: Crunch time. Changing Markets Foundation. December 2020. http://changingmarkets.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CM-WEB-DIRTY-FASH… quoting Eurobarometer 501 - Attitudes of Europeans towards the Environment. European Commission. March 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/survey/get… – the European Commission (2020) Attitudes of European citizens towards the Environment. Special Eurobarometer 501 Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/survey/get…

- 631.8% - https://apparelimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Taking-Stock-of-Pr… 10% - https://unfccc.int/news/un-helps-fashion-industry-shift-to-low-carbon These figures are put here to demonstrate the difficulty in finding accurate facts, not to support their veracity.

- 64Coscieme L, Akenji L, Latva-Hakuni E, Vladimirova K, Niinimäki K, Henninger C, et al. Unfit, Unfair, Resizing Fashion for a Fair Consumption Space Report. Hot or Cool Institute. 2022. https://hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Hot_or_Cool_1_5_fashio…

- 65Hoskins,TE. The Anti-Capitalist Book of Fashion. Pluto Press. August 2022 quoting – Interwoven Risks, Untapped Opportunities: The business case for tackling water pollution in apparel and textile value chains. CDP Worldwide. 2020. http://www.cdp.net/en/research/global-reports/interwoven-risks-untapped…

- 66Wicker, A The Fashion Industry Could Reduce Emissions—if It Wanted To. Wired. 13 November 2021 https://www.wired.com/story/fashion-industry-reduce-emissions/

- 67Wicker A. Will We Ever Be Able to Recycle Our Clothes Like an Aluminum Can? The New York Times. 30 November 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/30/style/clothing-recycling.html?smid=t…

- 68Changing Markets Foundation. Licence to Greenwash. March 2022 http://changingmarkets.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/LICENCE-TO-GREENW…

- 69Ibid

- 70Ibid

- 71Kent S. Norway Warns H&M, Norrøna Over Misleading Sustainability Claims. The Business of Fashion. 16 June 2022. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/sustainability/hm-norrona-no…

- 72Wicker, A The Fashion Industry Could Reduce Emissions—if It Wanted To. Wired. 13 November 2021 https://www.wired.com/story/fashion-industry-reduce-emissions/

- 74https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/729405/EPRS_BRI…

- 75Coscieme L, Akenji L, Latva-Hakuni E, Vladimirova K, Niinimäki K, Henninger C, et al. Unfit, Unfair, Resizing Fashion for a Fair Consumption Space Report. Hot or Cool Institute. 2022. https://hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Hot_or_Cool_1_5_fashio… – quoting data from Joint Research Centre, Institute for Prospective Technological Studies, Beton, A., Cordella, M., Perwueltz, A.et al., Environmental improvement potential of textiles (IMPRO Textiles) – , Cordella, M.(editor), Kougoulis, J. (editor), Wolf, O.(editor), Dodd, N. (Editor), Publications Office, 2014, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2791/52624

- 73Donald R. Patagonia Won’t Save the World Without Addressing Some of Its Prior Failures. The New Republic. 17 September 2022. https://newrepublic.com/article/167780/patagonia-wont-save-world-withou…

- 76Major brands are failing on living wage commitments. Clean Clothes Campaign. 14 June 2019. https://cleanclothes.org/news/2019/major-brands-are-failing-on-living-w…

- 77https://hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Hot_or_Cool_1_5_fashio…

- 78Hoskins TE. Foot Work: What Your Shoes Tell You About Globalisation. Weidenfeld & Nicolson; 2022. p165. There is an important difference here from ‘circular economy’ where economic considerations can take an equal place to environmental ones and can lead to outcomes like burning materials to make energy being more profitable than recycling them.

- 79Trashion : The stealth export of waste plastic clothes to Kenya. Changing Markets Foundation. February 2023. http://changingmarkets.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Ex-Summary-Trashi…