Corporate capture of our food systems: the importance of language

This is part two of our analysis exploring the corporate capture of food systems. You can read part one here.

As the climate crisis accelerates, the need for more resilient food systems – that centre human rights and can adapt to environmental challenges – is clear. Corporations and agribusinesses are claiming they can fix our broken food system, but, as we explored in part one, many of the organisations dominating the discussion on solutions are the same ones that created the problems.

Appropriation of the language historically associated with environmental and peasants' movements’ knowledge and practices is a key aspect of this process of corporate capture, and we have seen in the past how this can have important practical consequences. When organic farming became a popular concept, the term was co-opted by large companies and certification agencies, and organic certification became unaffordable for most peasant family farmers, particularly in Global South countries. Now, a similar process of appropriation is underway in relation to important terms like agroecology and family farming.

What is agroecology?

Agroecology is an approach to food production that centres people and planet over profit.

Agroecology can be variously defined as: a set of agricultural practices that aims to mimic natural processes; an approach to food production and economics that puts people and planet over profit; and a political movement that struggles for food sovereignty as a way of transforming food systems.

At War on Want, when we say agroecology, we always refer to peasant agroecology; an alternative to the model of corporate-led food production that drives peasant farmers out of their lands and keeps farmers in poverty. Agroecology has human rights at its core and represents a concrete set of solutions to the current climate crisis.

Our partners practice agroecology every day in their farming practices and political organising. In Kenya, our partners are developing alternative, organic pesticides that do not negatively impact the health of the local communities or biodiversity. In Sri Lanka, our partner MONLAR is building a new model of food production that centres the needs of the most marginalised farmers. In Bangladesh, BAFLF is identifying climate-resilient farming strategies. Whilst the North Africa Network for Food Sovereignty is providing political education for activists and farmers movements on the importance of agroecology and food sovereignty. And in South America, landless workers organisations and farmers are pursuing land reforms, building a solidarity economy, and fighting back against greenwashed solutions.

Peasant-farmers and movements all around the globe are fighting for their valuable knowledge to be recognised for what it is: a truly fair and just way to feed the world without exploiting people and planet.

Agroecology, the Corporate Way.

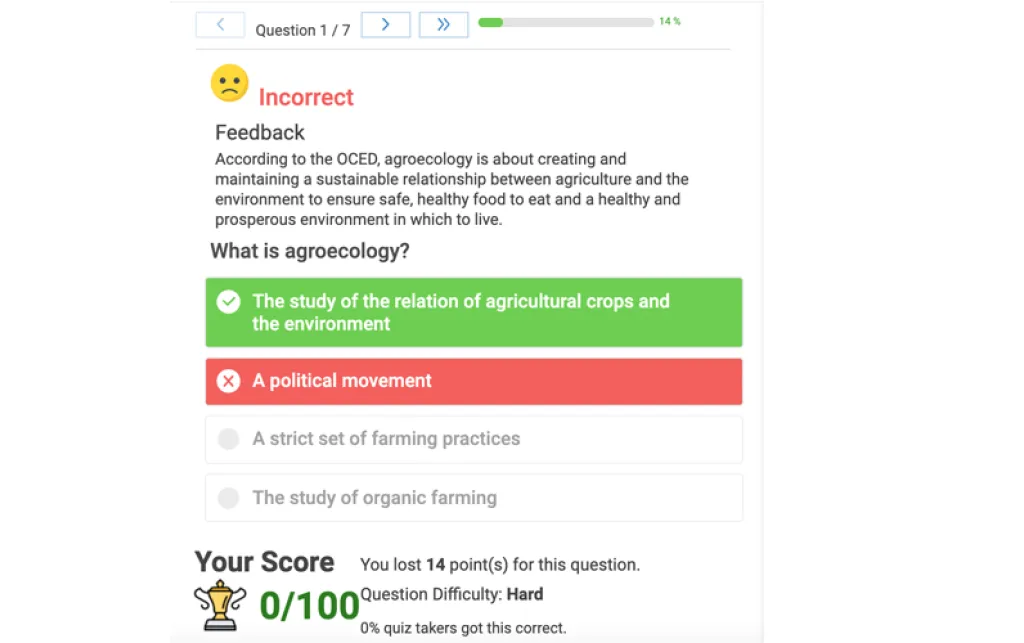

Today, many years after the term agroecology was first introduced by peasant farmers and their allies, the term can now be found in corporate strategies and guidelines for so-called “sustainable agriculture”. CropLife International, an industry association that includes some of the world’s largest and most harmful chemical pesticide corporations and agribusiness giants, have even created a “handy” quiz to spread a limited definition of agroecology. CropLife’s claim that it is simply "The study of the relation of agricultural crops and environment" is in stark contrast to the understanding of peasants’ movements around the world or to The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) recently published core principles of agroecology.1

When CropLife and others appropriate terms in this way, they tarnish the legacy of international peasants’ movements like La Via Campesina2 and their decades-long struggle for justice. Beyond this, they also actively create space for damaging policies and practices disguised under a veil of a supposedly sustainable initiatives. For example, CropLife recently submitted proposals to the UN Food Systems Summit (UNFSS), related to Integrated Pest Management – under the banner of agroecology – despite the fact their supposedly “sustainable” model of pesticides and chemical fertilisers are produced by the same small pool of corporations.

Family farming: reality over rhetoric

Family farmers in the Global South typically own small parcels of land or rent plots from larger landowners. As the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) states, family farming “is a mode of agricultural, forestry, fisheries, livestock and aquaculture production which is managed and operated by a family and predominantly reliant on family labour, including both women and men”. For Peasant famers’ movements, this term holds deep power and political importance:

“For us, family farming is peasant and indigenous agriculture; it is practised by families, true, but in connection to the community, with workers united to build the future.”

Agribusinesses, however, have increasingly defined family farmers as ‘tech-savvy families,’ who own large amounts of land, work at industrialised farms (often in the global North) and focus on monoculture commodities. Corporations claim these farmers thrive because they are supported by climate-smart technologies and synthetic pesticides that they sell them. In truth, large, industrialised farms are rarely run exclusively by families as they rely on underpaid and exploited agricultural workers.

At the same time, agribusinesses depict genuine family farmers, in the Global South, as “poor and food insecure [… with] limited access to agricultural know-how, services and markets’3. According to this dichotomy, family farmers in the Global South fail to thrive because they have not yet embraced the technological innovation of synthetic pesticides, GM seeds and digital tools.4

In reality, smallholder family farmers produce almost 70% of the food in the world, on approximately 25% of available agricultural land.5 The real issue is not about inefficiency or low yield, but about limited access to land, services, resources, fair prices and markets. These issues won’t be solved by a technology-only approach, but by transformational policies that place the rights of peasants and rural communities above corporate profit, prioritise the right to land and resources and promote seed sovereignty and fairer prices for small farmers.

Resist the capture: stand with movements

Understanding and amplifying the calls for food sovereignty from farmers’ movements around the world is the first step to resisting the corporate capture of our food systems. We stand with our partners in movements around the world who are fighting for a better system and for the rights of their communities. That means resisting the corporate takeover of their land, their livelihoods and their language.

Join us in standing with farmers around the world by sharing this article and taking action below.

1 http://www.fao.org/3/I9037EN/i9037en.pdf

2 https://viacampesina.org/en/what-are-we-fighting-for/biodiversity-and-genetic-resources/

3 https://youtu.be/D__yQebOsTM

4 https://agriculture.basf.com/global/en/sustainable-agriculture/partnerships/best-practice.html / https://youtu.be/HjQh9JT7rgs

5 https://etcgroup.org/whowillfeedus and FAO SOFA Report (2014)