Green technologies for people and planet

We are witnessing a revamped drive for a green economy. The transition towards an energy system powered by 100% renewable sources, and the so-called ‘4th industrial revolution’ of computer technology, big data and artificial intelligence, are being turbocharged by the prospect of multiple green industrial revolutions set to ‘kick-start’ the global economy as a response to the economic turmoil unleashed by the pandemic.

However, the logic and narrative of ‘green economy 2.0’ may not help us to deal with the ecological crisis. In fact, if uneven, market-driven renewable energy production and distribution, carbon capture and storage, and geoengineering continue to be accepted as viable solutions, humanity’s’ existential crisis could get a whole lot worse.

Transition metals: the new fossil fuels

Supported by the World Bank, the mining industry has positioned itself as key to the energy transition, claiming that it is needed to provide the minerals and metals to meet growing renewable energy demand. Yet, many of the same companies are heavily invested in fossil fuel extractors and are among the world’s highest corporate emitters.

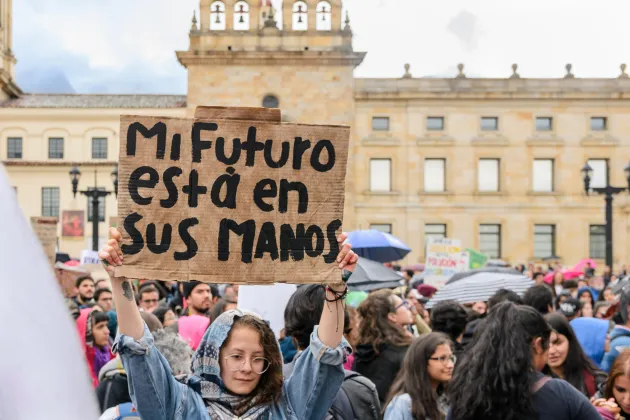

Frontline communities who have been resisting the expansion of global mining since the first commodities boom at the beginning of the century – and some argue, for many centuries prior – have warned that a drive for renewable energy technologies will do little to address the climate crisis if all they are doing is replacing the unequal and harmful ways in which energy is globally produced and distributed.

Unsurprisingly, the World Bank also considers Latin America as the primary potential supplier of transition minerals. It describes a shift in energy power from oil and gas producing countries, for instance in West Asia, to those able to supply materials for renewable energy, particularly in Latin America. The World Bank lists notable Latin American reserves including aluminium, copper, iron ore, lithium, manganese, nickel, silver and zinc. It also considers Africa a major supplier of these resources, with its reserves of aluminium, chromium, cobalt, manganese, and chromium.

One of the epicentres of the rapidly expanding green frontier is Chile. Home to the world’s largest copper reserves and 50% of the world’s lithium reserves – the country houses 80% of South America’s glaciers, which supply some 70% of the population with water for consumption farming, and sanitation.

These and many more climate-critical ecosystems have been ravaged by an extended decade of ‘mega-drought’, placing extraordinary stress on already-fragile water systems. The term ‘sacrifice zone’ is often used to describe the way in which communities, territories, entire cities or countries, could be left to wither away, with resources sucked dry and ecosystems desolate as a consequence of attempts to save humanity. The contrast is stark, but this has been the reality of industrial mining for centuries.

Anglo American: ravaging Chile’s glaciers and communities

One mining company has been under heavy scrutiny for the audacity of its claims about its role in tackling the climate crisis: Anglo American. The London-based multinational is one of the largest extractive corporations in the world, with a 2019 revenue of US$29.9 billion. In Chile, it has mining operations in three regions: Los Bronces in the Metropolitan region, El Melón in the Valparaíso region, and Collahuasi in the Tarapacá region, though its operations span across the globe.

Anglo American is not only known for the large amounts of minerals it extracts from the earth – which, incidentally, increased during the pandemic – but also for the socio-environmental conflicts that it has historically been involved in due to the direct harm it has done to communities and ecosystems at the El Soldado and Los Bronces operations.

Los Bronces, a giant mine at one of the world’s largest copper reserves, is already responsible for the ‘disappearance of two rocky glaciers’ and sucking up the water supply in the region, contributing to the ongoing historic drought. And yet, Anglo American is pursuing a $3.4 billion expansion project, tunneling underneath a glacier. It could spell disaster.

The communities affected by Los Bronces in the municipality of Lo Barnechea, together with the Corporation in Defense of the Mapocho Basin and Movimiento NO+Anglo have questioned the company about the expansion, claiming that it is dangerously close to the Olivares glaciers that source water to two rivers, the Maipo and the Mapocho, both of which are significant supplies of water to Chile’s capital, Santiago. At its last annual general meeting, the company announced that they did not consider glaciers as part of an ecosystem or as an essential part in water cycles.

Global supply chains, global solidarity

Each new green technology is a potential hotspot for extractivist violence and worker exploitation. From Chile to China, technological supply chains cover “mines, refineries, ports, ships, power plants, data processing centers, and entire cities that serve as capital’s logistical hubs”. Corporate supply chains are undergoing a planetary reconfiguration – but this also connects frontline communities, factory workers and floor shop assistants in chains of solidarity. Here we can find some hope.

Supply chains for these materials need to be strictly and equitable managed to avoid the plethora of negative social and environmental impacts on those least responsible for a climate crisis created by the Global North. Our movements must ensure that the demands of the essential workers and communities powering the renewable energy transition are foregrounded across value chains.

An upcoming report by War on Want will analyse the complexity of such supply chains, seeking to propose a path for supply chain justice – here we bring to light the key arguments.

Decoding supply chains

Firstly, a deeper understanding about criteria, standards and technologies is needed to ensure equitable global supply chains for renewable energy technologies, as well as the ethical procurement of these energies.

However, a globally accepted human rights standard covering transition minerals and the supply chains for highly complex transition technology simply does not yet exist. Supply chains extend to numerous tiers and to thousands of suppliers for components containing multiple metals mined across the globe.

So, monitoring an entire supply chain remains a major challenge.

The push for stronger due diligence

The risks associated with supply chains include a wide range of issues covering human rights, conflict, the environment, health and safety, transparency and corruption. The gravity of these concerns has meant that interest in responsible sourcing has gained momentum over recent years, with increasing interest driving both public awareness, and investor and consumer demand for assurances.

In 2019, the Investor Alliance for Human Rights called for enhanced investor due diligence to address environmental, social and governance risks throughout supply chains. The result is an expanding patchwork of interlocking legislation, norms and standards. Due diligence may be gaining more prominence, but the sheer complexity of the current landscape is raising as many potential problems as it solves.

The issue of due diligence in mineral supply chains covers more than just technologies focused on the energy transition. However, it is a key, and growing, sector of concern. According to research by the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, since 2010 there have been “197 allegations of human rights abuses related to renewable energy projects, [including]: killings, threats, and intimidation; land grabs; dangerous working conditions and poverty wages; and harm to indigenous peoples’ lives and livelihoods. Allegations have been made in every region and across each of the five sub-sectors of renewable energy development: wind, solar, bioenergy, geothermal, and hydropower.”

Source: Unknown

Transition minerals, similar to commodities such as palm oil or sugar, are materials that require processing. They are all easily mixed at the point of processing (unlike for instance diamonds or timber). Attempting to trace the materials to the point of origin (be it a mine or recycling plant) is a difficulty that must be overcome. This means that smelters and refineries are frequently the focus of attempts to verify the source minerals and provide a chain of custody in order to verify a mineral's passage through the supply chain.

CATAPA’s recent in-depth investigation into the lack of transparency and underreporting around the production of zinc and indium from Bolivia destined for European markets is just one piece of research that illustrates the opaque nature of processing and the challenges for responsible supply chains.

We need a strong, binding, international treaty

A number of new and varies due diligence initiatives are visible just beyond the horizon and are likely to impact future transition supply-chain transparency. The most important of these is the ongoing negotiation for an international legally binding instrument on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights.

Currently, although there are some relevant mandatory due diligence laws in certain jurisdictions, the majority of schemes are voluntary. The solution to this seems apparently simple, which is to make the OECD Due Diligence Guidelines mandatory for all companies operating globally.

Reducing demand: we need a Global Green New Deal

Although supply chain due diligence can solve some of the issues resulting from increased production of transition minerals, it is only a mitigation measure. If we are to avoid a severe rise in pollution and community conflict, particularly in the Global South, then we need to consider demand. A shift to renewables is necessary, but there are many ways in which that shift could play out.

Fundamentally, the solutions are social: technical fixes and increases in efficiency alone do not bring about justice or ecological well-being. A truly Global Green New Deal is an opportunity to put climate justice front and centre as the world enters a post-pandemic recession. However, this begins by ensuring that recovery or transition in the Global North does not happen at the further expense of ecological and worker well-being in the Global South.

This research is framed in the EC-funded Make ICT Fair project – Reforming Manufacture & Minerals Supply Chains through Policy, Finance & Public Procurement. CATAPA and War on Want are one of the co-applicants, which also include the University of Edinburgh, Electronics Watch, Sudwind (Austria), People and Planet (UK), SETEM Catalunya and Swedwatch.