Fashion is not an island – workers at the heart of a just transition

Just Transition is a principle, a process and a practice.”

The global fashion industry is not an island. Like many transnational corporations, the business models reflect a rigged economic system designed to maximise profit and amass wealth for the few, at the expense of the majority of people and of our natural world.

For 500 years, the capitalist logic of exploiting people and extracting limitless amounts of the Earth’s natural resources has fuelled slavery, colonialism and imperialism, creating a global economic system with the deepest of roots in racialised and gendered injustices. This embedded the idea that people and ecosystems in some parts of the world can be sacrificed because they have less value than those in the richest countries of the Global North.

Colonial powers such as the UK changed economic systems in the countries they colonised – from producing food to feed local populations, to producing cash crops for export to meet the needs of European countries. Minerals were extensively mined and exported from colonised countries, with companies adopting cheap and forced labour from the very communities that had been forcibly removed from the land. This extraction of resources and exploitation of labour, especially women’s labour in garment factories, continues today in the business models of big fashion.

Underpinning this rigged economic system are unfair and unequal trade and tax rules that leave Global South countries dependent on international loans and export-led trading models. Nations must then pay back unjust debts with crippling interest, as well as meeting the costs of ecological and climate breakdown that they did not cause.

These forces are the threads that hold big fashion together, and it is these threads that must also be unpicked to enable radically different futures for millions of farmers, factory workers, homeworkers, drivers, distributors and retail workers.

The urgency of the climate crisis has propelled debates about how to transition to greener ways of living. But for the transition of polluting industries such as fashion to be sustainable and fair, it means looking at the whole business model, and it means a re- visioning of the wider global economy from one that is measured through capital growth and profit, to one that is for the benefit of the majority of people, that works to protect the climate, nature and our ecosystems, and operates within planetary boundaries.

The Climate Justice Alliance describes a just transition as: “a vision-led, unifying and place-based set of principles, processes, and practices that build economic and political power to shift from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy. This means approaching production and consumption cycles holistically and waste-free. The transition itself must be just and equitable, redressing past harms and creating new relationships of power for the future through reparations. If the process of transition is not just, the outcome will never be.” 47

The previous chapter opened the possibilities of radical change that a degrowth approach to our economies offers. But the challenge of degrowth is also the equitable scaling down of energy and resource use, producing and consuming less and better to guarantee a safe and habitable planet. Richer Global North countries have to scale down in order for more globally equitable energy and material use, enabling countries in the Global South to have the productive capacity to meet human needs and achieve equitable development.

A just transition along ‘degrowth’ lines means removing the barriers for countries currently locked into fashion exports as their economic lifeline to make genuinely sovereign decisions about economic development and priorities. It means that the people who are dependent on fashion should be the ones the just transition protects and provides alternatives for. This is not a transition to save big fashion in its current profit-orientated form.

There cannot be justice in a future that puts the needs of garment workers anywhere but the centre, along with the farmers producing cotton and the homeworkers who are often hidden from consumer view. This is why intentions behind a just transition for the fashion industry must be rooted in global, purposeful, solidarity between movements of workers, and social and environmental movements. Any just transition must recognise and redress the harms already done through centuries of colonial-style enterprise that have stolen wealth, resources and labour from Global South countries.

Any discussion on a just transition to a greener economy must take place not on capital’s terms, but on labour’s. A transition to a more just and sustainable world is not possible by pushing more austerity on workers, or by forcing consumers to use greener products and materials. It is only possible through the payment of living wages for supply chain workers. It is only then a fundamental redistribution of wealth happens and without it, a just transition is not possible.

Principles of a just transition

Fair shares

A ‘fair shares’ approach means all individuals have a fundamental right to an equitable share of the world’s resources’ including the carbon budget for 1.5ºc, access to food, clean water, healthcare, education, and other basic needs. It recognises historical and current patterns of exploitation and injustice, particularly by wealthy and powerful Global North countries, and seeks to address these imbalances. It requires redistributive policies and mechanisms to redress global inequalities and disparities, such as Global North reparations for the climate crisis, including loss and damage, progressive taxation, cancellation of debt, and trade rule changes.

Countries of the Global North and their fashion companies have grown wealthy by accumulating profit ‘at home’ from the low-paid labour and overuse of natural resources of Global South countries. A fair shares approach would curtail corporate ability to extract wealth in this way, it would mean policies focused on ensuring those most responsible for climate breakdown pay the costs including through reparations and loss and damage funds.48

It fits with the model of degrowth, as those countries that have grown rich through the extraction of resources and labour would focus on degrowing damaging industries and investing in real climate solutions and sustainable alternatives, whilst poorer countries that have lost out are able to develop their own economic pathways.

Worker-led

Those most impacted should be the ones central to developing the policies to redress historic wrongs and build new equitable and just futures. This means ensuring that workers, and worker rights advocates like Kalpona Akter interviewed for this report, shape the discussions on how the fashion industry must change.

The right to join and to form trade unions is fundamental to worker-justice campaigns, whether as agricultural, land, factory, shop, distribution centre or home-based workers. A thriving trade union movement is the basis for workers in fashion to collectively have the power to negotiate for better wages and working conditions, and to exercise their labour rights. This is particularly important in the context of supply chains and as a crucial counterweight to corporate power.

Trade unions are essential to ensure workers’ interests and voices are influencing the policymaking process, representing the interests of workers, and advocating for a just transition. Trade unions can help to ensure that a degrowth-based transition is not only environmentally sustainable, but also socially and economically just. In this way, trade unions are critical to achieving a just and sustainable future for all.

Re-balancing power and re-writing the rules

The structures of the global economy have historically placed too much power into the hands of large corporations working to maximise profit and accumulate capital, enabling powerful elites to dictate the terms of business and trade.

Trade liberalisation has expanded corporate power and encouraged production and distribution through extensive and growing networks of global supply chains. Big fashion has been able to avoid accountability for conditions within supply chains and yield its power to force a race to the bottom to achieve the lowest production costs and maximise profit margins.

To facilitate a just transition of the fashion industry, we must stop trade rules from facilitating wealth extraction from the Global South. This means abandoning or strictly circumscribing trade deals, and revising or abolishing treaties, investment agreements and institutions that entrench corporate power and the domination of the Global South by the Global North. We must abolish Investor-State Dispute Settlement49

, which allow corporations to sue governments for pursuing public-interest policies that may impact a corporation’s future profits, and intellectual property rights that monetize climate-mitigation technology and put corporates in control.

Tax is a crucial form of government revenue, providing funds to invest in public goods and services such as health, education, infrastructure, welfare provision and climate mitigation. Yet the world is losing over US$427 billion in tax each year to international tax abuse. Tax Justice reported in 2020 that: “Nearly US$245 billion is lost to multinational corporations shifting profit into tax havens to underreport how much profit they actually made in the countries where they do business, and consequently pay less tax than they should. The remaining US$182 billion is lost to wealthy individuals hiding undeclared assets and incomes offshore, beyond the reach of the law.” 50

In the last decade a number of fashion brands have been exposed for tax avoidance including Next,51

Gap,52

Inditex,53

and Kering – owners of luxury brand Gucci.54

As profits are manoeuvred further up through the supply chains into the coffers of big fashion shareholders, Global South countries manufacturing garments sold to Global North consumers are effectively robbed of seeing the tax revenue from these highly lucrative sales.

This is not unique to the fashion industry, almost all global corporations are utilising tax policies, weaving complex webs through corporate structures to reduce their tax responsibilities. The problems are with both the profit-driven priorities of corporate giants, and the tax policies that enable them to move money around to minimise tax liabilities for profit.

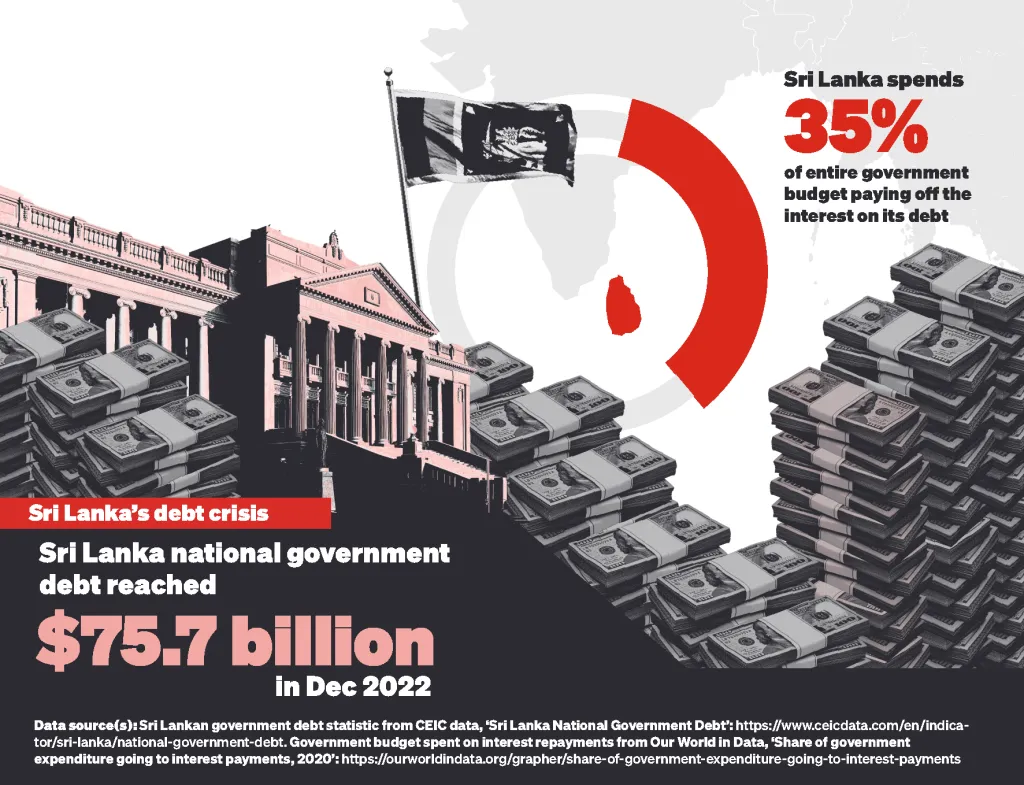

Debt plays a huge part in the economies of garment-producing countries such as Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Vietnam. Governments around the world borrowed heavily to meet the costs of tackling the Covid-19 pandemic. For those countries already servicing heavy debts, the costs of the pandemic tipped them into economic crisis. In 2019, the total global debt owed was already as high as US$101 trillion55

, rising to US$226 trillion in pandemic hit 2021.56

For Sri Lanka, international debt is a key driver of the political and economic storm that has unfolded since 2022. The country’s reliance on foreign investments from private and state lenders, and loans from international financial institutions including the IMF, means the Sri Lankan economy is particularly unstable.

Along with heavy borrowing, Sri Lanka political leaders implemented policies of deregulation and cutting taxes for the wealthy and creating low-tax privileges for foreign investors. Combined with the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, which ripped through Sri Lanka’s already fragile, debt-laden economy, ravaging the key tourism, plantation and garment export industries; Sri Lanka was toppled into debt crisis.

The cancellation of unsustainable debts for countries such as Sri Lanka will be a prerequisite for any just transition that will impact workers in a key export industry such as fashion.57

With all that is wrong with the fashion industry, it is clear that fashion corporations cannot be trusted to lead the way towards a just transition of their industry in line with the principles set out above. The experiences of other polluting and exploitative industries, such as food and energy, illustrate that those who have an interest in maintaining the status quo are not the ones to provide either the vision or the motivation for alternatives.

The workings of the global economy demonstrate that the neoliberal political and economic institutions that dictate trade rules, debt management and tax policies cannot lead the way. Their interests lie in preserving the very systems that have accelerated inequality, poverty and climate breakdown – and have laid the foundations for countries of the Global South to be treated as sacrifice zones as the ‘solution’ for continued profit-driven economic growth in an era of ecological breakdown.

Building the power and connections of movements globally is key to holding governments and corporations to account. Civil society organisations at the frontline of dealing with the human and environmental costs of corporate greed are able to vision alternatives that meet community needs, and that can reverse ecological damage and work within planetary boundaries. They have been living the impacts of poverty, inequality, loss of biodiversity and ecological breakdown in their communities, and can see how these intersecting crises have materialised.

Workers’ associations, organisations and trade unions are able to champion the rights of workers and act as a counterbalance to corporate power, and are key to advocating for workers’ rights in international policy spaces. Putting forward the voices of those who are most directly impacted is crucial to ensuring the transition of any exploitative and polluting industry is based on justice.