The global impact of the fashion industry

Fashion should be about art, creativity and the creation of beauty, but it’s none of that right now – at least not for tens of millions of people. Workers who make clothes should get to feel like they’ve created something of beauty, yet nobody feels that.”

How to make clothes

Humanity faces a fashion challenge: eight billion people need to be clothed and shod in a way that does not cause ecological havoc or human suffering. This report is dedicated to lifting our collective vision to consider radical alternatives – such as degrowth – which would transform our clothing system to leave a lighter touch upon the Earth, and erase the misery inherent in garment production. If this report can join the dots between the crises of climate, inequality and poverty, and offer an alternative way of managing this industry, why does big fashion itself not do this?

The short answer is because we live under a capitalist economic system that is not based on human need or minimising damage to the planet. The system we live under imposes an inappropriate measure of how to use what we have to fulfil human need: profitability. In the words of New York economics Professor Richard Wolff, interviewed in this report: “If it isn’t profitable, it doesn’t get done.”

Profit accumulation is at the heart of capitalism and the fashion industry. It is what drives the race to the bottom, pushing labour and environmental standards down and down, culminating in factory fires, and collapses – and rivers dyed blue and orange by toxic chemical run-off.

Big fashion brands exist to make maximum profits for the people who control them. This is why solutions will never come from the industry itself and we cannot afford to continue looking in the same places for ideas. Instead, this report seeks new perspectives on how we should decide fashion’s future, and in so doing; decide the future of life upon this planet.

Shifting threads

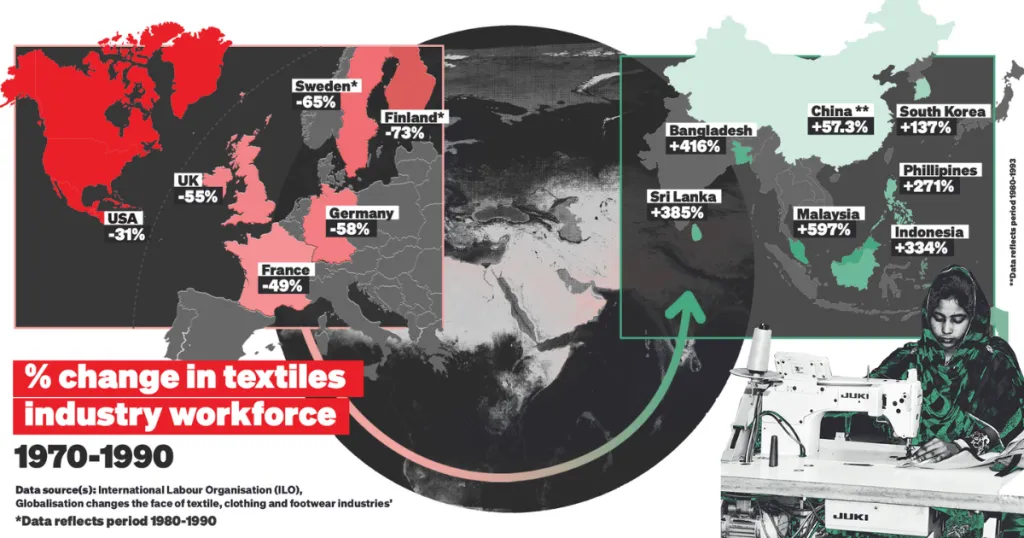

A key reason profits are so high for big fashion corporations is because of how clothing is produced. The decades between 1970 to 1990 saw the production of clothing, footwear and textiles shift across the globe in search of lower manufacturing costs and lower environmental regulations. The industry in Europe and North America suffered huge job losses, while Asia in particular experienced major job gains. This shift changed not just where clothes are made, but how much people are paid to make them – and the conditions that they are made in. The entire industry transitioned from the formal sector into the informal sector, with negative consequences for workers’ wages and conditions.5

This globalised shift continues to shield people in the Global North who buy fashion from the pitfalls of production: worker exploitation in factories, poverty, abuse, rock-bottom wages and soil and water pollution. Instead, countries in the Global South are left to deal with the impact of the fashion industry.6

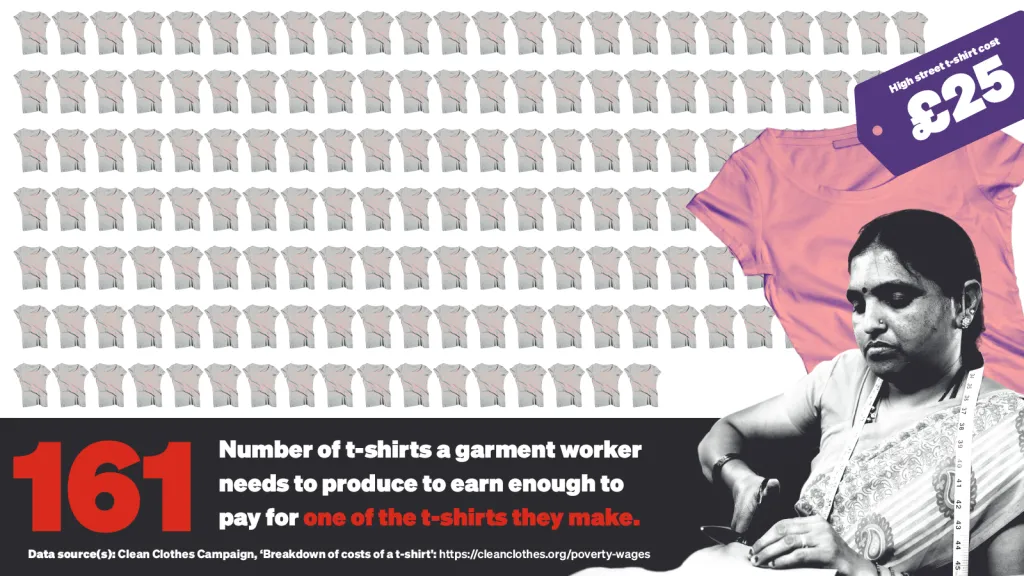

Breaking down the cost of a €29 t-shirt, the Clean Clothes Campaign found that while profit to a clothing brand and materials each accounted for 12%, or €3.61, payment to the worker who made the t-shirt was just 0.6%, or €0.18.7

Fashion production currently employs an estimated 4.2 million people in Bangladesh, with clothing and footwear production accounting for 80% of all Bangladeshi exports.10

This over-dependence on garment exports is the result of Bangladesh being steered into the fashion industry by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, which wanted Bangladesh to abandon hopes of self-sufficiency and open up its economy to global markets.11

After independence in 1971, Bangladesh’s economy was characterised by strong trade restrictions, including high tariffs on imports, to support a strategy of import-substitution (an economic policy that prizes domestic production over foreign imports). While the 1980s saw a moderate relaxing of this strategy, in the 1990s large-scale trade liberalisation was implemented as a cornerstone of neoliberal economic dogma. Trade liberalisation benefitted the garment industry as exporters were provided with easy access to credit, low import taxes on machinery and tax rebates.12 Big fashion meanwhile gained access to a labour pool comprising millions of impoverished people.

Forty years on from the start of trade liberalisation, Bangladesh remains in this precarious trap, creating vast profits for some of the most powerful multinational corporations in the world, yet unable to achieve financial stability. It is a prime example of national ambition thwarted by neoliberal ‘solutions’ that were only ever designed to be a dead end.

Becoming economically dependent upon a single product is “a recipe for economic disaster,” explains Professor Wolff. “Capitalism is an extremely unstable system. Every four to seven years on average capitalism has a crash, which means periodically your industry zooms up and then it zooms down, it has a good year and then it has a bad year. But if you’re a country that just exports garments, you don’t have any flexibility, you’re an entire society focused on one commodity – the product controls you rather than you controlling the product.”

When crisis strikes, countries are forced to borrow money from banks and financial companies, from other countries, or from global institutions such as the IMF. When the time comes for this loan, or even just the interest on it, to be paid back, a new drain is created on an already poor society. When commodity prices fall – as we saw with fashion during the Covid-19 pandemic – more money must be borrowed, and the cycle of debt continues.

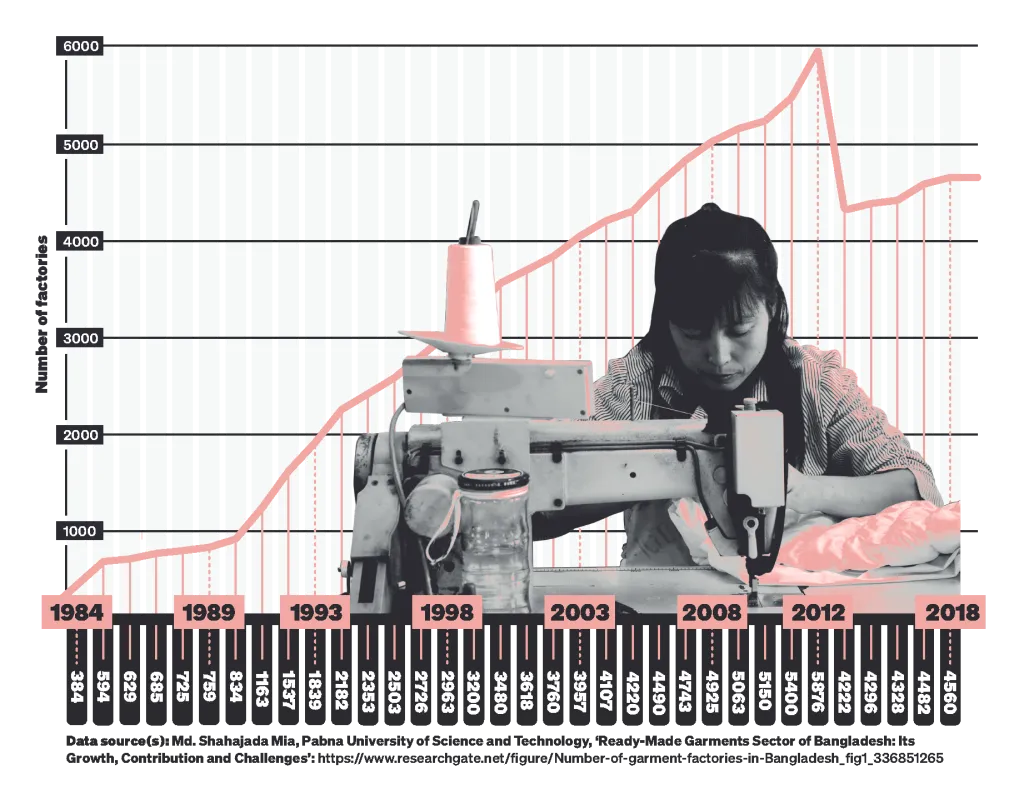

Textiles factories in Bangladesh

In the late 1970s, Bangladesh had an estimated twelve garment factories. By 1985, there were 450 factories, and by 2015 there were 7,000.8 By the 1990s, the factory workforce was 90% women, and Bangladesh was hailed as an economic success. But the women stitching hems, snipping threads, and folding and pressing garments were paying a high price, both physically and emotionally. Between 2005 and 2012, more than 500 people died in factory fires and collapses in Bangladesh.9 Then in 2013, 1,138 people were killed in the Rana Plaza collapse.

Colonial pathways

The British Empire shaped the world through slavery, colonialism, military aggression, and financial power. In the process it amassed vast wealth through a deliberate policy of deindustrialisation and then wealth extraction. Professor and economist Utsa Patnaik calculated that between 1765 and 1938, Britain drained US$45 trillion from India.13 (For perspective, Britain’s entire GDP for 2018 was approximately US$3 trillion.14 ) These centuries of looting built British infrastructure, while causing incalculable damage to the socio- ecological fabric of communities across India.

Today, big fashion follows these colonial pathways to industrial sites where safety standards can be evaded. Nandita Shivakumar of the Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) describes the fashion industry as “an extraction of wealth from the Global South in terms of land and labour”. This, she says, “ranges from non-payment of wages, the lack of a living wage, to pollution and gender-based violence. This extraction is utilised for both big fashion and consumers in the Global North. This neocolonial system does not help develop local industry and it certainly does not help workers.”

Liability troubles

When production shifted to the Global South in the 1970s and 1980s, clothing companies rushed to take advantage, paying workers rock bottom wages and maximising production to pile clothes high and sell them for less, creating demand and fulfilling supply to drive profits higher.

The clothes were not of course affordable for the people making them – one study found that a worker in China doing a 50-hour week would have to spend half her monthly wage to buy a pair of Nike trainers.15

Before the globalisation of clothing, many Global North companies manufactured their own products in factories they either owned or had very close relationships with. But with production now subcontracted to the Global South, clothing companies stopped manufacturing and concentrated on building brands instead.

This severed the official link between corporations and their legal liability for the way their products were produced. Fashion corporations tried to shrug off responsibility by branding themselves as ‘buyers’ rather than primary employers, as if they did not control virtually every aspect of the production process. In their endeavours to build brands, efforts went into PR machines to repair reputations, over fixing bad practices. It has taken decades of campaigning to re-establish, and continually fight for, the fact that corporations have a duty towards the people who make their clothes and a responsibility for how those clothes are made.

Yet it remains extremely difficult to hold big fashion accountable, making the fashion industry a dangerous, destructive, highly polluting place. “It is almost impossible to hold a brand liable in a production country, yet nor can we really hold them liable in consumption countries,” explains Shivakumar. “It is not a feasible economic fight for a Global South union to go to the US, find a lawyer, and fight with these huge brands.”

Competition

As well as profit and a lack of company liability, competition shapes the fashion industry. Big fashion corporations compete to make the highest profits, while countries compete to supply big fashion.

“There is so much competition between countries,” Shivakumar continues. “Asia should be seen as a region, but countries compete with each other for contracts, and within a country like India, states compete against other states.”

Professor Wolff concurs: “It has become relatively easy to buy and install machinery to make clothing, and the skills needed to work these machines are fairly easily taught, so it becomes a struggle in which factory owners in India, China, Bangladesh, Vietnam and so on compete to produce the sneakers, blouses, underwear, socks for the market. They are in a primitive, ruthless competition.”

If factory owners are all submitting bids for contracts to make shirts, and are all in competition with each other, how do they achieve the lowest bid? “They do it by gaining an advantage they can translate into a lower price,” Professor Wolff explains. “They have to find the cheapest workers, they have to work them mercilessly, they can’t have a union, and they can’t rent or build a safe building.”

If factory owners are all submitting bids for contracts to make shirts, and are all in competition with each other, how do they achieve the lowest bid? “They do it by gaining an advantage they can translate into a lower price,” Professor Wolff explains. “They have to find the cheapest workers, they have to work them mercilessly, they can’t have a union, and they can’t rent or build a safe building.”

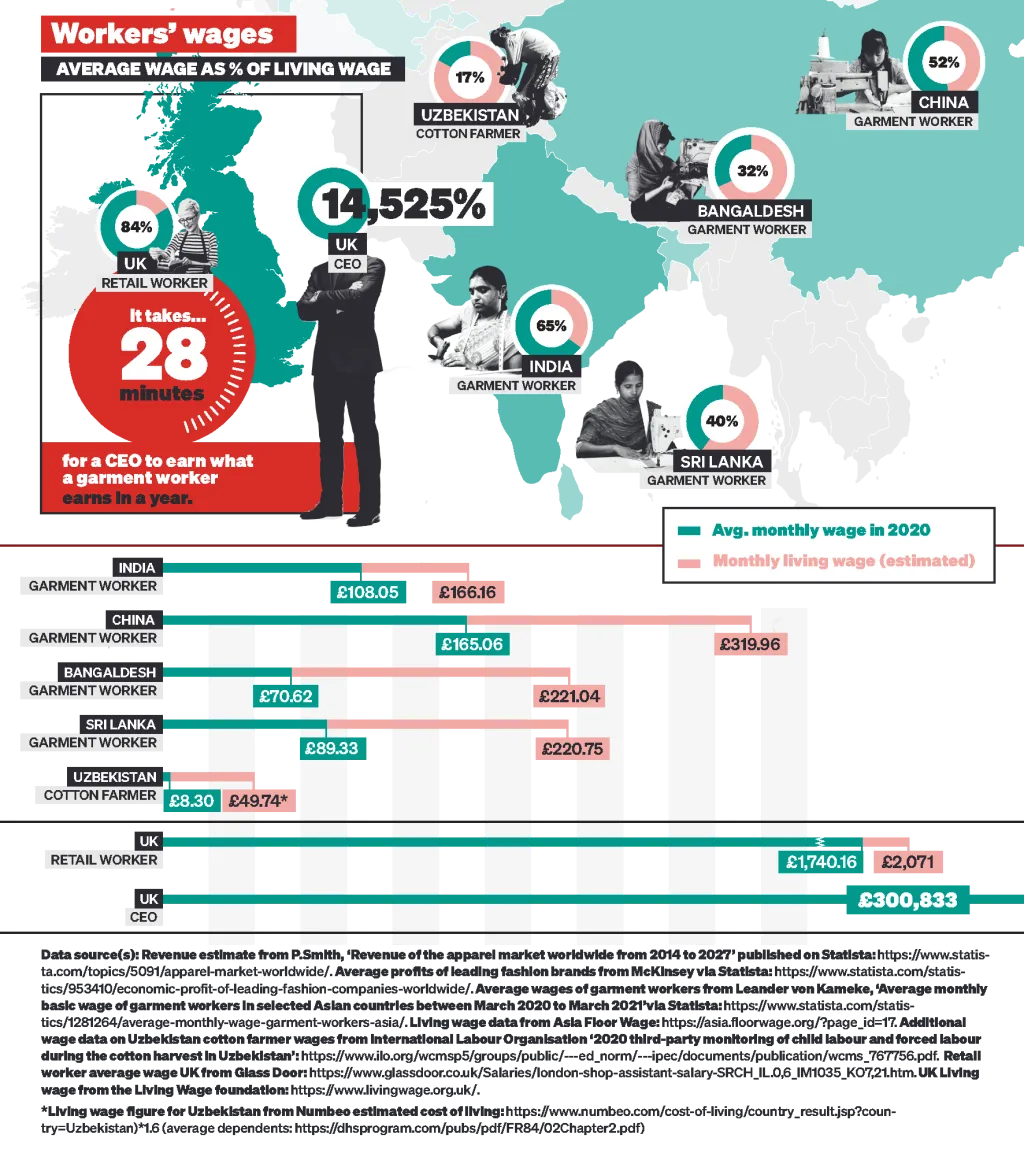

Ongoing research by the Clean Clothes Campaign has found that, as of 2023, there aren’t any major brands, either fast fashion or luxury, which can prove all workers in their supply chain earn a living wage. “No garment or sportswear company recognises that brand business practices have a direct effect on workers’ wages, leaving millions of workers deprived of not only wages but sleep, access to health care, safe transport, the ability to live with loved ones, adequate food, education, even time poverty from needing to work extra hours.”16

Meanwhile, it takes the average fashion company CEO just 28 minutes to amass what a Bangladeshi garment worker earns on average in a year.17, 17

These factors – the pursuit of profit, lack of company liability, globalisation, colonialism and competition mean that behind the scenes, the fashion industry is a violent system at every turn. From endemic gender-based violence, to climate violence and state-sanctioned oppression of workers and unions by police and paid thugs, to intentional neglect as a form of violence – as seen at Rana Plaza. Professor Wolff describes this violence as “the lubricant of the whole system,” something that is ever present rather than a particular event.

At its heart, the fashion industry is built on injustice, and would not exist without the exploitation of women, of the Global South, of migrants, of people of colour, of the land and our collective natural resources. But the violence that accompanies this exploitation is also a sign of a system in flux, of people unwilling to put up with the unfairness of the system – wherever there is oppression, there is also resistance.