Fashioning the future

When these people start discussing green deals or carbonless economies, do they lose their minds? Don’t they know the truth about workers and what could happen to millions of people in the production countries?”

The world is in a state of crisis. Climate breakdown, unprecedented global inequality, the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and global cost-of-living crisis, are ravaging the lives and lands of the world’s poorest and most marginalised communities. Increasingly frequent and intense climate disasters amplify and deepen these existing inequalities, with devastating consequences for millions of people.

Inequality, both within and between countries, has become deeply entrenched – the result of centuries of colonial plunder and dominance of a rigged economic system that has seen the wealth of rich elites grow exponentially at the expense of the majority. The gap between the richest and the poorest is stark: half of the global population share just 2% of global wealth, while the richest 10% own 76%.1 Just 2,153 billionaires hoard more wealth than 60% of humanity.2

These are global challenges, demanding urgent transformation of our economies and societies, including polluting industries like fashion. Yet the opening words of this report from Kalpona Akter should challenge all global justice movements, especially those in the Global North, to recognise that it is the voices of the people and communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis, that must shape the transition we are striving for.

The global fashion industry, or as we call it in this report, ‘big fashion’, is controlled predominantly by corporate elites in the Global North, and is part and parcel of an economic system designed to maximise profit for the few, at the expense of the lives and livelihoods of working people across the world. The clothes we wear, and the processes that produce them, therefore provide us with a window into the broader inter-connected crises of poverty, inequality, climate and ecological breakdown.

Radical alternatives such as degrowth movements offer different ways of envisioning industries like big fashion. Degrowth questions the relentless extraction of resources and exploitation of peoples in the pursuit of corporate profit, proposing that those most responsible for climate damage must reduce production and consume less. The idea is to prioritise moving to a socially just and ecologically sustainable society with social and environmental well-being replacing gross domestic product (GDP) as the indicators of prosperity.

This report honours those working in the supply chains of an industry notorious for exploitation and abuse, both of workers and of our planet’s eco-systems. The report is not a blueprint for how to transform big fashion, but an insight into how the business model and economic system they operate in are inherently damaging. It situates the fashion industry as a key sector that must be urgently transformed because of its impact on the planet, and explores the extent to which corporate power and pursuit of profit has driven profound inequality, poverty, and worker exploitation. Crucially, this report explains why the transformation of sectors like fashion must be designed with and by workers and frontline communities, and not become another crisis they must endure.

In 2013 the Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh killed over 1,100 people and brought public attention to the devastating human cost behind the polished shopfronts and websites of both high end and high street fashion brands. Today, ten years on from Rana Plaza, big fashion is increasingly under scrutiny as a leading culprit of our ecological and climate crisis, as well as its continued exploitation of workers.

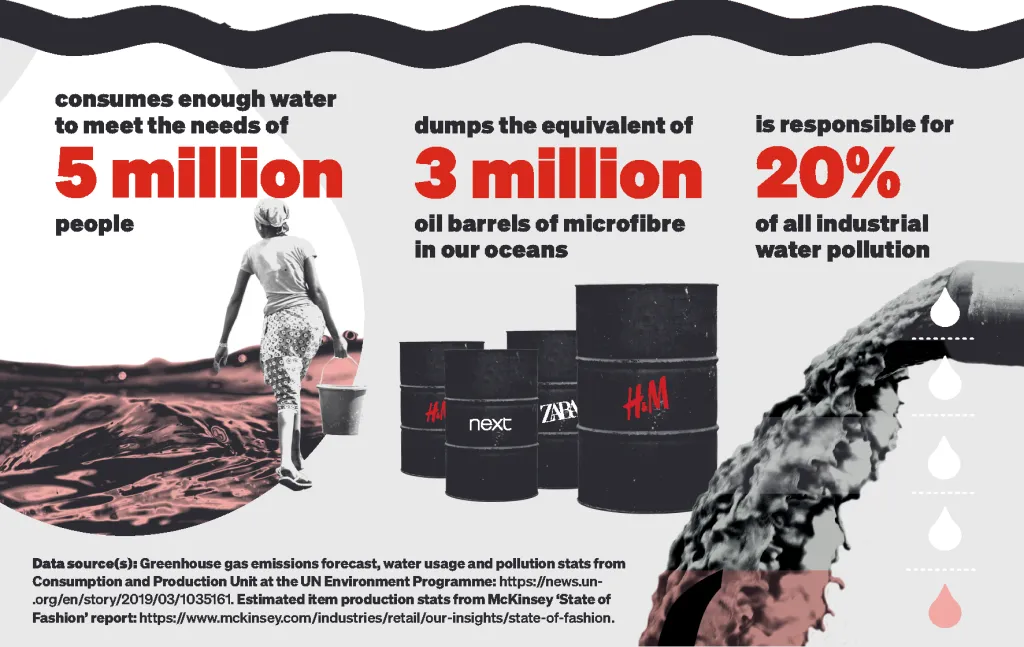

Big fashion is pushing our climate beyond critical warming levels. There is a lack of reliable data regarding fashion’s ecological footprint – estimates of greenhouse gas emissions generated by the industry range wildly from 1.8% - 10%.3 This is an industry that runs on a lack of transparency – and places little value on the people and ecosystems that it exploits.

Fashion’s social and environmental crimes have the same systemic causes yet frequently solutions appear to present polarised choices between ‘workers’ or ‘planet’. Environmental movements call for consumption to be drastically reduced or ended for the sake of the planet. In return, economic justice and workers’ rights movements highlight the economic consequences and impact that millions of job losses would have on the fight against poverty and the right to a dignified life for many across the Global South.

While this polarised debate continues, corporate capitalism is free to greenwash its own survival narrative that will leave its power and profits fundamentally unchallenged, and our world blighted by poverty, inequality and spiralling climate violence.

Much of the sustainability narrative of the fashion sector to date has been focused simply on shifting away from the energy sources that fuel processes of garment manufacturing. Indeed, many garment- producing countries have sought to expand their own fossil fuel-based industries, not with the primary intention of meeting the needs of their citizens, but in order to produce ‘cheap energy’ for the industrial sectors. Yet, the fashion industry remains unaccountable for the environmental impact of this expansion.

The fashion industry drains water and other critical resources from Global South countries, contributing to rapid soil depletion, land systems change and biodiversity loss.

This ecological breakdown is driven by the profit motives of corporations based in the Global North, but it is the world’s poorest and most marginalised communities that suffer from the devastating impacts of continued resource extraction. As we will see in Chapter Five, big fashion is inseparable from the issue of land ownership and pollution – land stolen and shaped by colonial conquests and land ravaged by the corporate thirst for export crops.

This process of extraction from the Global South results not just in ecological impacts. It also systematically deprives the South of the resources required for key infrastructure and development. Resources that could be used to meet essential human needs are instead appropriated for the sake of corporate expansion in the Global North, perpetuating a cycle of inequality and deprivation.

The same underlying systems and structural drivers propel the dual crises of inequality and ecological breakdown. It is vital that our response takes account of this by offering transformative, intersectional solutions. That is why our vision is of a radical alternative in the form of a Global Green New Deal that centres the voices of workers and those most impacted, that offers a pathway for a just recovery from the climate crisis in ways that guarantee everyone’s right to live with dignity by tackling the systemic causes of poverty, inequality, structural oppression, and ecological breakdown.4

Building the power of intersectional movements with fashion’s workers at the heart, is the way to bring forward the bold visions and radical demands that can transform fashion beyond the swapping of materials, to the uprooting of injustices and the power monopolies of its corporate elites. This report offers us a starting point for an alternative way in which to approach a just transition, in a way that appropriately apportions responsibility, and challenges us to re-think what we value the most.

Asad Rehman

Executive Director, War on Want