PART 1 – THE STATE OF THE GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEM

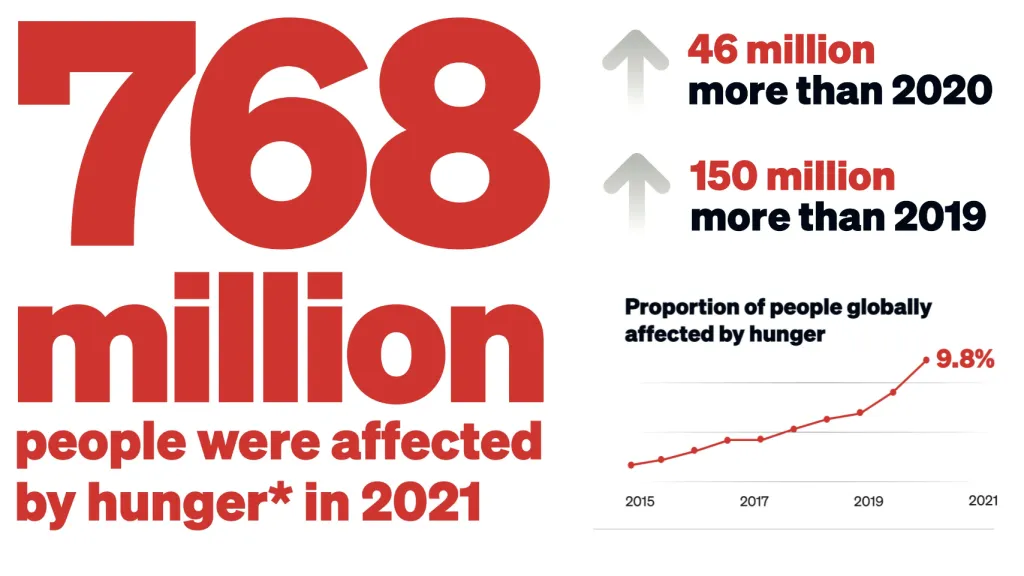

World hunger is once again on the rise, following the numbers of those experiencing hunger falling between 2009-2013. This trend has now reversed, with global hunger increasing year-on-year: in 2021, more people were affected by hunger than in 2020, which had increased from 2019.2

It is because of the global agricultural and food – or agrifood – system, itself susceptible to political and economic crises, that the rural poor, who produce food, are going hungry. Hundreds of millions of small-scale food producers, from pastoralists to fisherfolk, from Indigenous forest dwellers to those tending small oasis plots face hunger and states disinterested – if not hostile – to their right to a dignified life free of hunger.

Many governments around the world continue to reject small-scale peasant farming and agroecology as a pathway to feeding their populations. The idea of a different global agrifood system based on national food sovereignty is dismissed in the belief that large corporate monopolies in agricultural and food production will be more efficient at solving the problem of hunger. Those fighting for transformation confront greedy monopolies, which also control and profit from the chemicals and machinery that go into food production. However, this model of food production, based on monoculture, the intensive use of energy and chemical inputs, and genetically modified seeds, is unsustainable both for the Earth’s biodiversity, its climate, and its people.

The global food system has been completely transformed over the last 50 years. Agrifood systems in the Global South have supported, supplemented, and supplied the North in the name of ‘food security’, alongside unprecedented land acquisition and hunger – despite increased production. This is the vision of food security, promoted by governments in the Global North, supported by northern food and agricultural monopolies; with further support from Global South agribusiness elites and plantation owners, who profit from producing for the North, while draining wealth and health from people and land alike.3

This transformation of agriculture and food systems over many decades is tightly connected to the intersecting crises of poverty, inequality and injustice, and climate breakdown. This context, together with widespread inequality regarding access to land, is the long legacy of colonialism and imperialism throughout much of the Global South.4

Under colonial rule, farmers in many parts of the Global South were coerced into growing crops for export such as cotton, wheat and sugar, to satisfy the food demands of the colonial power, for which farmers received low prices. In recent years, food security concerns have led to large-scale land grabs by richer countries, a form of ‘agricolonialism’, to secure food supplies for their own populations. Added to this is the corporate capture of the whole food system from seeds to markets, with financial markets speculating on food prices and farmland entrenching a colonial mindset of relentless extraction, exploitation, and profit on enormous scale; regardless of the impact on the people working to produce food, or to the planet and our ecosystems.

With scientific studies finding that between 21% and 37% of all greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to the food system, the impact of the current industrial model of food production on the climate crisis cannot be underestimated.5

The climate crisis is the most pressing ethical and political issue of our lifetime, with less than ten years left to keep global heating to a maximum of 1.5°C to avoid catastrophic climate breakdown. As it stands, scientists are already indicating that measures to tackle the climate crisis will not meet the guard rail of 1.5°C.

Increased global heating will have a severe impact on biodiversity and ecosystems, including species loss and extinction. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that of 105,000 species studied, 6% of insects, 8% of plants, and 4% of vertebrates are projected to lose over half of their “climatically determined geographic range”, once global heating hits the 1.5°C mark. A rise of 2°C will make the situation much worse. Fewer species means dramatically reduced global biodiversity: this would place a strain on already vulnerable food systems, especially agroecology, which relies on a functioning biosphere.

The IPCC has warned that the climate crisis is already affecting food security in a number of regions, with the risks of disruption to food systems growing.6

It also warns that just transitions are needed to ensure approaches to climate mitigation that do not result in competition for land with communities losing out. Low-income producers and consumers are likely to be the most affected due to a lack of resources to invest in adaptation, mitigation and diversification measures. The speed at which the Earth is warming means that farmers have little time to successfully transition their agricultural practices to build resilience, if that is even possible, through agroecology.

The challenges are immense, which is why a full and just transformation of the global food system to a model of food sovereignty is needed.

1.1 The colonial legacy of export-oriented agriculture

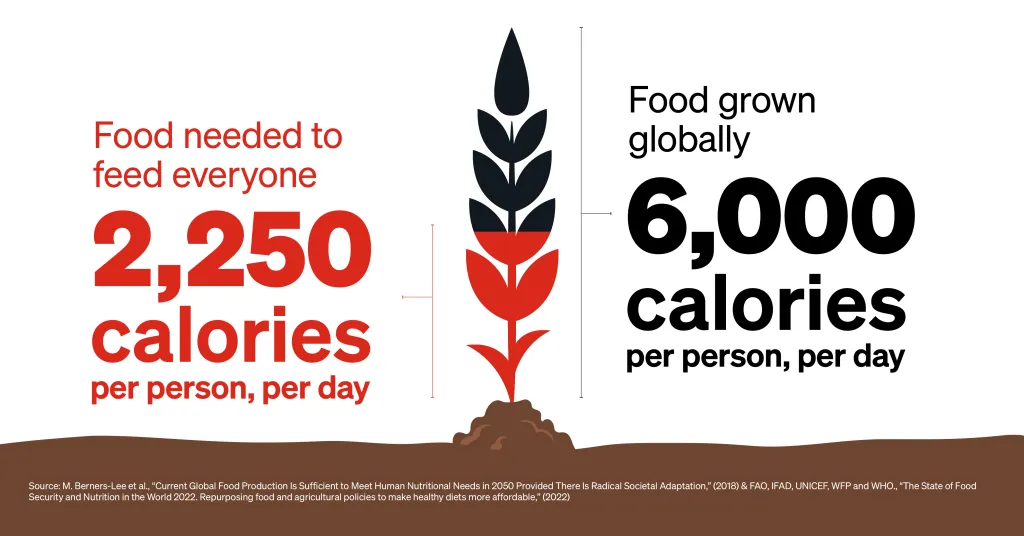

The crisis of increasing global hunger, and of the world agrifood system itself, is not due to a lack of food, nor a lack of technology or land: it is not a crisis of overpopulation.

It is a crisis of how food is produced, and of sharply unequal power relations along global North-South lines, and within countries themselves. Those who are powerful enough to control food production determine who consumes it and who goes hungry. Because of this power imbalance, people are poorer and hungrier in the Global South than in the Global North, and it is in the South where struggles for food sovereignty are more pronounced.

The global agrifood system has its roots in colonialism, imperialism, and monopoly capitalism. In the 1970s, the combination of imperialist policies and monopoly capitalism produced a new regime called ‘neoliberalism’, which marked a return to colonial power imbalances. As an example, even by the end of the 19th century, poorer colonised countries including India, Sri Lanka, Ghana, Indonesia, and Brazil specialised in tropical-climate produced exports such as spices, tea, and coffee – ungrowable in northern climates regardless of technological advances.7

Colonialism saw the mass acquisition of land. To grow and export cash crops (crops grown for their commercial value rather than for the grower’s subsistence and use) and tropical goods in countries where the native population was hungry but also powerless, it was considered logical to concentrate land in as few hands as possible. During this period, per-capita consumption of cereals in Global South countries continuously decreased: in effect, starvation by colonialism.8

Existing state-centred systems of famine prevention evaporated under colonial control, leaving countries across the tropical and sub-tropical regions vulnerable to the whirlwind of hunger, poverty, and mass death.9

By the early 20th century, grain production began to be concentrated in countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, as well as some Latin American countries, where land had been made available by the genocide of Indigenous peoples.10

National liberation movements erupted in the 1940s to the 1970s across Global South countries including Kenya, Algeria, and India; these movements began freeing land and taking important steps towards national agricultural models, but seldom broke with the focus on commodity exports.

The United States produced a vast amount of surplus food in this period, particularly cereals.11

This overproduction saw the country embrace a new food dumping strategy, with cereals sold at reduced prices on international markets and exported globally. By the 1970s, many countries in the Global South began switching their agricultural efforts towards exports through ‘free-trade’ agreements with Global North countries, even while the national aspects of their agricultural and production systems were affected by costly and often imported agricultural inputs, such as fertilisers, herbicides, tractors, and animal feed made from barley and corn, as the Global North globalised its model of capital-intensive (requiring large capital investment) industrial agriculture.12

US food corporations grew ever more powerful.

With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, systems of national agricultural production were mostly dismantled across the former Soviet states, which led to a huge reduction in available food per person, and mass death from hunger.13

FOCUS: Trade deals and food dumping strategies

‘Free-trade’ agreements exposed Global South agriculture to cereal dumping strategies from industrialised countries.

Under the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, US capital-intensive maize production was exported to Mexico; devastating local milpa production, a form of peasant agriculture based on the integrated cropping of corn, beans, and squash.14

This move effectively turned Mexico into an open-air greenhouse for US fruit and vegetable consumption,15

while displaced Mexican peasants became workers in US domestic agribusinesses.16

The destruction of Mexican smallholder agricultural production through the ‘opening up’ and erosion of protections around domestic production facilitated large grain traders’ export of crops, and local US agribusiness’ import of people. The destruction of the Mexican people’s right to food and a dignified life is therefore linked to cheap crops produced for the consumption of US consumers, and to massive ecological disruption.

Milpa agriculture is sustainable, and harbours abundant genetic biodiversity, with hundreds of maize subspecies often flourishing in a single plot: it is a productive, resilient agricultural practice, resistant to drought, flooding, blight, and pests. A typical full-time milpa farmer produces enough calories to feed around twelve people, including themselves.

By contrast, industrial US corn production concentrates profits in the hands of corporate agribusinesses. Only a tiny variety of maize subspecies are grown, making crops highly vulnerable to diseases, pests, and climate breakdown; and far more energy is used in producing the corn than the crops contain. Some researchers have characterised this as a shift in agricultural approach from using “sun and water to grow peanuts” to “using petroleum to manufacture peanut butter”, turning the traditional logic of agriculture upside down.17

The shift from peasant-based agroecology to corporate-based monoculture has led to a decline in crop resilience, ecological biosecurity, and energy efficiency, while increasing profits for large corporate agribusinesses.

Milpa production is emblematic of Global South communities’ small-scale yet critical reliance on the environment for food production. Around 2.5 billion people live to varying degrees off the land.18

According to a recent study, small-scale farmers holding less than 10 hectares produce a minimum 55% of the world’s food supply on 30%-40% of the world’s arable land. Other research shows that around 70% of the global population is fed or dependent on peasant farming, on just 30% of agricultural land.17

1.2 Food waste to global greenhouse emissions: an unsustainable model of food production

The amount of waste produced by the global agrifood system is widespread and systemic. Although some countries waste relatively little food – even major economies with large populations such as China - other countries such as the US with its vast and complex purchase, processing, and distribution chains, lose half of the food produced between farm to fork.20

It is not just food itself that is wasted. Food production lays waste to the environment: while between 21% to 37% of global carbon emissions caused by human activity come from agrifood systems, the predicted greatest future increases in agrifood sector emissions will come from global supply chains, rather than farming itself.

Emissions calculations from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), estimate these future increases to be even greater if emissions generated from agricultural fertilizer manufacturing are included, along with food processing supply chain emissions (packaging, transport, retail, household consumption and waste disposal).21

Shortening and re-localising food supply chains is increasingly important. The Covid-19 pandemic illustrated how local markets and short supply chains are much more resilient amidst moments of crisis.

The Green Revolution of the 1950s to the 1970s promoted the intensive use of pesticides and a monoculture model of agriculture that has been proven to be unsustainable and unequal, both for the biodiversity of the planet and for peasants in the Global South. This unsustainable model of food production is based itself on the overexploitation of natural resources, which reduces soil fertility and biodiversity;22

it causes dependency on large amounts of agricultural inputs, requires vast amounts of external energy, and makes production more expensive – and peasants more economically dependent. This system is less resistant to changes in weather patterns and to the growing climate crisis. It creates increasing inequality and poverty in rural areas, as peasants are more dependent and reliant on fewer crops, and more exposed to the fluctuations of prices and external markets.

1.3 War, imperialism and hunger

War and conflict are increasingly devastating the Global South, directly affecting food production, distribution, and local populations’ access to food – especially those displaced by conflict. This has resulted in widespread hunger and increased malnutrition: the decade between 2011 to 2021 saw global hunger skyrocket. In the Arab region, the continuing impact of war and protracted crises (characterised by periods of ceasefire, interrupted by open low- or high-intensity warfare) across Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen has seen hunger rise sharply.

However, the story is one of missing numbers. Wars produce widespread hunger and famine, while undermining the capacity to accurately count and reach the hungry.23

People’s rights and access to food in the context of war and conflict is affected by a range of factors: income, the security of food production, the state of active warfare in their country, access to global grain markets, and any international embargoes and sanctions. Yemen is one of the most war-blighted countries on the planet, yet has sufficient food stored in warehouses24

and growing in fields to supply the entire population with enough food to eat. However, people are too poor to afford it. Widespread poverty, made worse by years of war, is the result of a long process of national underdevelopment and lack of support for local agriculture, along with creeping corporate-monopoly control of the Yemeni agricultural system.25

The US-Saudi-led operations in Yemen’s conflict have directly affected rates of poverty across the country.26

Poor Yemeni farms have been directly targeted, meaning there is less food for sale on local markets, while families find themselves forced to buy what they used to be able to produce at home.27

The lack of respect for the Yemeni people’s right to self-determination, to self-government, has created one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, with 19 million people suffering from food insecurity.28

1.4 The climate crisis and post-Covid landscape

The global food system is inextricably entwined with the Earth’s biodiversity and climate. The mounting urgency of the climate crisis means food production is already seriously vulnerable to climate impacts. The rise in global temperatures threatens to exceed planetary limits, with changes in precipitation patterns, more frequent droughts and heatwaves, rising sea levels and deadly floods all threatening food production.

Crops and livestock struggle to survive when conditions become too hot and dry, or too wet and cold. Extreme climate disasters such as droughts, floods and cyclones destroy crops and land, and are leading to huge numbers of displaced people in countries most at risk of catastrophic climate impacts.

According to The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), weather-related hazards displaced 24.9 million people across 140 countries around the world in 2019, many of whom were agricultural workers and small-scale peasant farmers, who lost both their homes and livelihoods.29

For Global South countries, the impacts of climate breakdown compound increasing poverty and intensify pressure on already scarce resources, which can lead to instability and conflict.

The interconnected nature of these crises is having devastating consequences on peasant farmers, as the inability to mitigate climate impacts increases the risk of low yields, the sudden reduction in agricultural productivity, and even the complete loss of crops. Over the longer term, it can lead to the degradation of soil and large-scale damage to land, rendering some areas unsuitable for growing crops, disrupting local markets and resulting in rising food prices, further entrenching poverty and hunger.

In Tunisia, a major food importer and exporter of fruits and vegetables, many people are no longer able to buy locally-reared and grown chicken, beef, or pomegranates, amid severe inflation and soaring food prices.30

The effects of the war in Ukraine, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the climate crisis have also played their part: 2020 saw Tunisia’s economy contract, with cereal products rationed, and long queues forming outside bakeries. Ships bringing cereals from Spain and Romania idled outside the southern port of Sfax, as the government searched for the hard currency to pay its suppliers.31

Against this background of Covid-19 and conflict, new dynamics are in play across the global food system. New corporate entities have emerged, implementing new strategies of accumulation and techniques of co-optation. Innovation in technology has concentrated power and ensured the agrifood system continues to be dominated by monopolies. Corporations have newly entered international public policy spaces, such as the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

Various net-zero initiatives, such as carbon credits, are being proposed in an attempt to find ways to adapt and mitigate to the impacts of the climate crisis. However, such initiatives are developed to fit within the same model of large-scale agribusiness focused on profit, within the same approaches to international trade and trade agreements, preserving the same power dynamics; meaning large multinationals and other powerful stakeholders are dictating the terms. This risks the financialisation of land and greater land concentration into fewer hands, damaging the planet, citizens, and farmers alike.32

The presence of the World Economic Forum (WEF) or representatives of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation at global food summits demonstrates the advancement of the monopoly capitalist agenda and the hollowing out of existing institutional spaces. ‘Nature-based climate solutions’ (see Chapter 3.3) and dietary interventions are promoted, as is the role of ‘sustainable intensification’ in supply and value chains,33

while land grabs are naturalised.

The global model of food production has benefited large corporations based in the Global North the most since the dawn of the Green Revolution.34

In the last decade, corporate power has increased, including in global public policy spaces: corporations have either entered food spaces such as the FAO, or other United Nations (UN) organisations, or constructed their own, as with the World Economic Forum – subverting the rights to food and just development.

There is, however, some hope, as peasant movements are growing and connecting with other important struggles. Food sovereignty movements are much stronger than the scattered groups 25 years ago, organised now behind international networks such as La Via Campesina and The Civil Society and Indigenous Peoples’ Mechanism at the UN Committee on World Food Security. Movements are more connected and more engaged in working in public policy spaces to make effective changes at national and global levels. They are also crucial voices in climate policy spaces.

Small-scale farmers are the ones already putting 70% of the food on our plates, whilst using only 30% of the global arable land. They have the know-how to work towards sustainability but not the resources to overcome the challenges put in place by those who wish to maintain the status quo for their own benefit.”